The research sprint: (Re)Designing research funding processes

ProtoPublics has been designed as an experimental project, exploring how to engage people from different academic disciplines, as well as others such as community groups, activists, or local government, in doing design-oriented collaborative research. This has involved the research team (myself, Guy Julier and Leah Armstrong) working with the AHRC to try out ways to develop small-scale, collaborative proposals for research funding through a faster-than-usual process. It builds on recent research council programmes such as Connected Communities, which aimed to bring together researchers from different disciplines and others from community or research user organisations.

This post discusses how the approach we crafted compares with the well-established sandpit model for developing cross-disciplinary research projects. It also reflects on what didn’t work in the way we hoped, and how we think our approach should be changed. My hope is that this discussion will serve other designers of research funding programmes that aim to support collaborative, cross-disciplinary, innovative, design-oriented research.

In the sandpit

As described by the EPSRC, sandpits are “residential interactive workshops over five days involving 20-30 participants; the director, a team of expert mentors, and a number of independent stakeholders. Sandpits have a highly multidisciplinary mix of participants, some active researchers and others potential users of research outcomes, to drive lateral thinking and radical approaches to address research challenges.” The sandpit model was developed to support cross-disciplinary research to generate novel research approaches, consortia and projects. Programmes using this approach include those addressing climate change, gun crime and empathy and trust in online communities.

In contrast to the usual ways that academics develop and apply for research council funding, the sandpit model is “a wonderful opportunity – but only for those who were up for it – to engage in creative, intellectual play with ‘Socratic dialogue’”, according to organisational psychologist Bharat Maldé, who worked with the EPSRC to develop the approach.

The way the format works is that individual researchers form into teams during the workshop, define research questions and design and develop projects to address them. They receive feedback to hone their research proposals, and then may be invited to apply for ring-fenced funding which is only available to people who participated.

Research councils continue to experiment with formats. For example in the Connected Communities programme, the research development workshop that was held in March 2014, lasted three days. Participants were then able to apply for up to £100,000 for projects developed at the workshop.

The percentage of total funding awarded to UK researchers via sandpits is small, but it is a large amount in absolute terms. According to Judy Robertson writing in the Guardian, in 2013 just one council, the EPSRC, spent £218,000 on sandpit running costs, and allocated £19.4m on research to be funded from sandpits, 2.5% of its annual research budget.

However criticism of the sandpit approach recognises how it relies on participants being “up for it”. For example it disadvantages people with caring responsibilities who find it hard, or impossible, to be away on a residential workshop for five days. As a parent of a young child, I have been unable to attend sandpits I was invited to, resulting in my not being able to apply for the funding or shape the conversation about the research.

So in the design of the ProtoPublics project, we wanted to address these concerns. Further, from the social sciences and Participatory Design, we recognised that the design and facilitation of any event has a kind of politics. The ways the event is organised, staged, facilitated and resourced enable and open up particular kinds of engagement and participation, and close down others. To borrow terminology from sociologist Steve Woolgar’s (1990) study on how users are constructed, workshops “configure” their users in particular ways. Rather than claiming our event was a neutral space for researchers to come together to develop proposals, we recognised our roles in co-constructing this with them and with the funder, and were attentive to how the workshop enabled us to have different kinds of agency. We therefore intended for our design and facilitation to be reflexive about the kinds of research and researcher it was privileging and enabling, even as we tried to help create new kinds of research.

Designing a research sprint

In the ProtoPublics project, we decided to build on aspects of sandpits and also borrow some of the principles underpinning other kinds of exploratory format. In the design of our “sprint” workshop, we were inspired by events/processes familiar to those of us working in design, service design and design for social innovation such as

- Global Service Jam and GovJam: two-day workshops, often organised by volunteers, at which people come together to come up with new solutions to a collective challenge

- Hackathons or hack days: practical workshops involving people coming together developing new (often digital) solutions to address an issue

- Asset-based approaches that start with recognizing and building on the resources available to a community

- Agile software development, that emphasizes light documentation, many iterations, responsiveness, and a focus on use. The term sprint comes from a version of agile called Scrum. During a sprint, a development team work together with the aim of producing “shippable” (ie ready to go to market) software by the end of it.

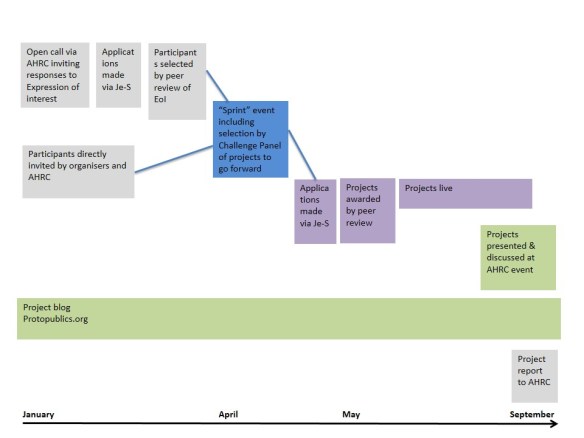

The process we developed for the ProtoPublics project was bounded by the conventional research council application process through which eligible research organisations would (if selected at the sprint workshop) be able to apply for ring-fenced £15,000 grants via the Je-S electronic submissions platform. Within the existing constraints, we shaped this process as follows:

- We invited (short) expressions of interest (EoIs) to invite people to join the event. The EoI was sent out by email the AHRC and also publicised on twitter by the ProtoPublics team and by others. The event was open to researchers (ie academics) from organisations eligible for research council funding, as well as practitioners. However few of the latter were likely to receive it via the AHRC’s usual communications channels. We received several expressions of interest from design practitioners, artists and arts organisations, but none from community groups, local government or consultancies.

- We seeded the sprint event by inviting academics and practitioners from different fields to attend, many of whom were involved in the previous project we undertook for the AHRC, Mapping Social Design (2013-14).

- We developed and populated a public blog, which included clips and text from interviews we conducted with people whose perspectives we thought are relevant to the aims of the project.

- We designed a two-day sprint workshop held in Lancaster based on these principles: that it would be agile, collaborative, creative, participatory and reflexive.

- We did not finalise the funding call before the sprint event. Instead the AHRC used discussion and challenges from participants in the workshop to rework the call, for example changing timings and some of the requirements applications needed to meet.

- During the event, eight research consortia/teams self-organised and went through several iterations of developing and revising proposals. The feedback they received was from other participants, from members of the Challenge Panel to whom they presented on day 2, and (in relation to the application process), from AHRC staff.

You can see the event agenda and some photos and a capture of the Twitter stream here.

In the end, five projects that were initially generated in discussions at the workshop were awarded funding via peer review after making applications via the research councils’ Je-S platform. Each of these has been awarded £15,000. They will do their research over the summer and each present at an AHRC workshop in September. Some of the participants, including James Duggan and Emmanuel Tsekleves are blogging about the project:

This blog remains an important part of the project, which the five research teams can use to share their projects and reflect on the conditions and infrastructures that support innovative design-oriented research.

What we learned

In this post, I will focus on what did not work well and what we could have done differently, which goes to the heart of how this approach is different from a sandpit.

During the sprint event, teams did not at first come up with the variety and novelty of proposals we hoped for, although the premise of ProtoPublics and the size of the awards was to enable experimentation. At several points in the process, academic participants who are used to larger research budgets told us, “We can’t do much with £15k”. However we continued to assert that the point of this research call was for researchers to try out something new, take some risks and try to do things differently, including over short time frames such as a couple of days or a week. This lack of experimentation, we later reflected, was shaped by three factors.

Firstly, those participants familiar with the Je-S application structure were likely to be guided by the way it orders research projects. Those participants, especially those who were principal or co-investigators awarded grants on big schemes, such as the Connected Communities programme, were shaped by particular modes of thinking about and doing cross-disciplinary research of the kind awarded funding.

Secondly, we realised our own design and facilitation of the sprint was partly responsible for the lack of variety and novelty. For example, half way through day 1, we asked people to begin to define a shared research question and then come up with ways to address it. This resulted in participants falling early on into conventional ways of thinking about research – what’s worth doing, how to do it, who to involve and what impact it might have.

Thirdly, we were not successful in getting a wide variety of participants to participate in the event. Yes, there were people from many different institutions, disciplines and specialisms, and not just in the arts and humanities. But several of the design and arts practitioners we had invited, as well as people from small businesses and local government, did not take up the invitation. So not having these different voices present as participants – whether as ‘users’ of research, or as people doing other kinds of research practice – meant the group as a whole did not experience substantial challenges to the nature and purpose of research.

What we’d do differently in the next sprint

Reflecting on the Lancaster event and the research proposals it generated, we concluded we could have made better use of the resources in the workshop/process and the networks in which participants were embedded, if we had further pushed the agile and other principles we drew on.

First, we could have enabled participants to focus on recombining the resources they had access to – the so-called asset-based approach – in relation to the funding resources available. Although our sprint event started with an activity to map the assets of those present, we did not make further use of this approach. For example it would have helped if we had materialized a typology to help participants (and ourselves) make sense of the diversity of projects, knowledge, relationships, expertise and outputs connected to participants in the room. Further, although we organised an “ideas market” during which participants had a structured opportunity to connect by moving around the room and talking to one another, again this did not produce some of the radical collisions we had hoped for.

These two activities were intended to help participants engage with one another and use that as a basis for developing projects. We could have more strongly guided them to recombine their resources to craft a project. Instead of the conventional approach of deciding on a research question, and then defining an approach to explore or answer it, the sprint could have explicitly reversed this. By starting with what they already do/ask/have/know as resources, participants could have crafted projects that combined their assets in novel ways to contribute to their individual research agendas by assembling a shared one.

Second, we could have guided participants to be more explicit about the nature of their possible research collaboration. One of the principles of the sprint in software development, is producing an output. In the context of research, this would not be working software, but it could be materializing a mock up of the research process or domain.

During the sprint, members of the Challenge Panel suggested to participants to make use of some of the materials and studios made available to us by our hosts at Imagination Lancaster. Although some of the participants responded negatively to the challenge from by one panel member of “being more designerly”, it was striking how some of the teams responded positively and creatively to this opportunity. For example one team, later awarded funding, used cardboard and other materials to create a sculptural form of the Dewey organ they want to make. Such bricolage came late into the sprint event, and could have been integrated more strongly to push teams out of their conventional project-designing practices into seeing how materializing their ideas changed them.

Thirdly, we could have designed ways for a range of participants to critically assess and challenge other people’s proposals. ProtoPublics was weakened by the absence of having research partners or users in the workshop, other than on our invited Challenge Panel (which included Nicola Hughes from the Institute for Government and Cat Macaulay from the Scottish Government) and a very few arts-based organisations as participants. We did structure in team-to-team peer review sessions during the sprint. But when sitting in on several of these conversations, we heard polite, collegial friendliness, rather than the critical reflection we were hoping for – let alone the brutal feedback of unhappy customers.

In Lean Start-up, the concept of the Minimum Viable Product is the idea that an entrepreneurial team should launch as soon as it can a minimum set of functions they think customers will value, learn from testing this proposition with customers, and then potentially pivot – ie go in a different strategic direction depending on the results. Loosely adapting this – while recognizing that such market-driven ideologies are not appropriate for research – we could have asked teams to develop “minimum viable research proposals”. Instead of a research outline, already ordered to be Je-S compliant, in which participants crafted their ideal project and then squeezed it into what could be done with the resources available, the lean approach pushes for multiple iterations in a short time-frame with regular feedback from customers. We think we missed an opportunity here to explore what an iterative development of an asset-based, minimum research proposal could look like.

To conclude, our team’s reflections during and after the sprint event have helped us see that the approach we applied did materially and discursively do something different to current models of cross-disciplinary research development. Our project design and facilitation contributed to the emergence of five strong proto-projects that have been funded. We hope others will take forward some of these ideas in the design of funding programmes and engage in dialogue with us and the AHRC. Yet with the principles (and ideologies) we borrowed come other limitations and implications, to which we will return.

Dr. Lucy Kimbell

Celia Lury: Developing participation in social design: suspending the social?

Celia Lury, ESRC Professorial Fellow and Director of the Centre for Interdisciplinary Methodologies, University of Warwick, made a provocation presentation entitled ‘Developing participation in social design, suspending the social?’ at the AHRC ProtoPublics Sprint Workshop on the 16 April. She has very kindly shared the slides from her talk with us here: Social design

A Q&A between Sue Ball and Guy Julier

Introduction

This ‘conversation’ is a summary of discussions between Sue Ball and Guy Julier in March and April 2015, culminating in their live Q&A at the Lancaster ProtoPublics workshop. This blob is a a redaction of material exchanged between them during that period. The Q&A is structured around two projects that Sue has been engaged in which raise different issues.

Sue Ball is Director of Media and Arts Partnership, Leeds, a public art consultancy that doesn’t do ‘landmark sculptures’ or public artist community engagement programmes. Rather it works closer to complex, sometimes design-led, urban regeneration processes. She was Director of Pavilion in Leeds 1996-2000 and has worked on cultural strategies for engaging citizens in Rochdale and Oldham and with town teams in Scunthorpe and North Allerton. Sue developed a body of work to support interdisciplinary learning, including cross disciplinary peer review and action research, in the ‘making of place’ (2009-10), and to explore ‘the act of listening and our sensory relationships with the city’ (2010-12). More generally, she has worked between the development sector, local government policy, creative practices and academia (though she has never worked in academia).

Sue and Guy Julier worked together as directors of Leeds Love It Share It, 2008-10, a registered Community Interest Company that continues to operate as an open forum for ideas, debate and action in Leeds, aiming to create new visions for how Leeds could be in the future through research into community skills, social networks and the use of local assets.

Banging Heads Together: LLISI

GJ: In Leeds Love It Share It (LLISI) there were seven of us as company directors: ourselves, Paul Chatterton and Rachel Unsworth from the School of Geography at the University of Leeds, the architect Irena Bauman, Katie Hill from Design at Leeds Metropolitan University and Andy Goldring who is CEO of the Permaculture Association. We were motivated by a critique economic and cultural direction of Leeds and its leadership and the challenges of the triple crunch of climate change, global economic crisis from 2005 and Peak Oil.

We went very quickly from being about manifestos and ideas to actually getting involved in a community-based, publicly funded project. Sue, you raised nearly £100k for it from the then Regional Development Agency, Yorkshire Forward (YF), and the Local Entreprise Growth Initiative (LEGI). I think there were a number of challenges:

- Interfacing between diverse interests/stakeholders/organisations such as YF, LEGI, LCC, neighbourhood, interest groups, regeneration and health arms length organisations while carrying forward an explicit political agenda that was critical of neoliberal status quo held by dominant power interests in the city;

- Learning to work cooperatively in a cross-sector team with different expectations of research practices and outcomes.

A number of other questions arise here. Was it knowledge-focused or were we looking at producing something more tangible? And if it was knowledge-focused, what were some of the conditions that facilitated this? How did we construct these conditions?

SB: We came together informally to develop interdisciplinary praxis as an independent think-tank, to forge a new set of alliances to challenge regeneration planning and policy orthodoxies in Leeds City Council, and to create an open learning environment through practical engagement that offered up our collective practice and processes for broad external review and critical peer appraisal. Some of this was published as a paper in City Journal and as a extended working ‘toolkit’ document (2011).

Due to my previous interest in structuring open reflexive interdisciplinary learning, there’s couple of things that I brought to the table that facilitated knowledge generation I feel.

In terms of the policy context, political leverage and sector buy-in (whole systems appraisal), you mentioned my producer role in raising funding. As important it was to secure buy-in from mainstream commissioners of regeneration services such as Leeds City Council and the Regional Development Agency, in a way that was participative and permissive. A positive attribute of the RDA funding was that there were no specific outcomes required, only a report. The offer from our side was to include them in the process of the research and to allow them to interrogate it as an embedded participant, which offered reciprocal benefits. A further merit of their investment was their badging of the scheme and the honorific value of association which prompted higher status policy-related conversation at city and regional level in response to on-the-ground community-facilitated regeneration in East Leeds.

We initially structured the 12 month research programme that included review and appraisal days. These were held quarterly and were programmed by the team to allow thinking and work in progress to be presented and debated. These sessions brought policy makers and service commissioners together with member of the Richmond Hill community, activists and academics within a broad constituency of stakeholders to consider how land, property, skills and network capacities at a local level could be appreciatively re appraised to generate forms of sustainable resources and assets. These sessions enabled the LLISI team to reflect on research methodologies, visual communication tools, and learning derived from field studies, and to finetune delivery according to emergent opportunities. This structure also built trust with local people and councillors who initially viewed LLISI as yet another set of professionals landing on the community.

Summary of Issues Arising from LLISI

- how to declare the intention of the broker (issues of neutrality?)

- that funding and agendas drive outcomes/outputs (hard negotiations to secure permissive flexible funding)

- should deliver locally, act locally, but understand policy and include policy makers (whole system appraisal)

- bring different stakeholders together into structured dialogue to unlock their own internal dynamics and resources (infrastructure development)

- visual communication is key – how to develop well researched (often visual) data and information in a form that works for the end-user as advocacy/lobbying material, or to articulate systems and what’s happening now and next steps

- need to challenge commissioners and funders to re engineer funding programmes that recognize changing conditions – bring them in as co-producers

- co-production elements stitched in were very beneficial – how to structure reflective learning environment

- connected community practice with academic input, but at times this did feel awkward

- important learning and formative experience for all LLISI members.

Dodging and weaving: Warwick Bar

GJ: I’m a bit of a fan of dodging and weaving as a research method. This means that you adopt an open and flexible approach to developing a practice and accounting for it, producing or prototyping innovations along the way.

You’ve been working with developer ISIS Waterside Regeneration on their Warwick Bar scheme in Digbeth, Birmingham since 2010 where I think a lot of this attitude has been employed in your way of practising. Can you tell us a bit more about this project?

SB: I’ve been working with developers for about 10 years now and in particular Isis Waterside Regeneration and developer Mike Finkill. Warwick Bar is 2.8 hectares, with 43,000 sq ft of lettable space, and about 15 mins walk from New Street station on Birmingham in Digbeth, post industrial & heavy manufacturing base. In 2010 there was only 20% of the site occupied. I was invited to work with Mike and I requested that we should start by working closely with the commercial agent Colliers International. I organized joint visits to Glasgow Spiers Lock and other sites where there was a different more proactive relationship with tenants. We developed a number of ways of re-activiting the space such as small physical interventions over time, responsive relationship with tenants and Open Doors events to wide constituency of arts, third sector, community people to welcome ideas for usage.

The commercial agents default setting is to focus on forcing up the commercial value of property. But we developed a Meanwhile Licensed Use of 45 days to enable R&D activities, which levered a 6 month business rates ‘holiday’ on each industrial units (3 months on offices). I took the units under license through Art in Unusual Spaces CIC, of which I’m a Director, and the savings were transferred to me which I used to commission artists and cultural activity. Up to last year, I leased units under 45 day license and through this internal economy, commissioned a wide range of arts and cultural agencies to use the units and public spaces such as Companis, Cathy Wade, Homes for Waifs and Strays, Flatpack Cinema etc. I also wrote a Meanwhile Use Policy, which was adopted by the Client, that all empty units should be offered up through the website for meanwhile use.

GJ: This sounds a bit less experimental than the LLISI work?

SB: I think working closely with developers certainly was less ‘activist’ in its roots, but within the project there were several gaps and openings to develop new processes and relationships. I’d summarize these as follows.

- Licence Innovation Another innovation in licensing was to develop ‘nomadic leases’ which offered a 10 year licence to agencies that wanted land for growing and cultivation, without this lease security, they can’t fundraise. We might have to move within the site if development take place. For instance Edible Eastside.

- Meanwhile Use as a Strategy I’m critical of meanwhile use, short-termism and hidden economies of the pop-up. This license and use demonstrates an alternative and a win-win situation for both the client and cultural economy. The site was only 20% occupied four years ago – now almost 100% with no hard marketing needed – mostly word-of-mouth testimonials.

- Judicious Interventions Starting out, I went out to connect with the Birmingham cultural sector and met with Ikon Gallery who were looking for a mooring for their 3 year arts/youth programme Slow Boat. We jointly developed a mooring space that in turn created a more amenable public realm. The public realm and canalside locale was used for summer and winter events drawing in audiences from Digbeth and the city. We have developed a very collegiate culture of co-operation onsite and this has been achieved in part by responsive intervention and also by encouraging all tenants to open their doors and programme for the public events in the summer.

- Dense Networks Warwick Bar/Minerva Works is now a densely interconnected complex of design, architecture, arts, fabricators & printers (commercial and not-for-profit) with Clifton Steel steel sheet producer as its anchor tenant. Key arts agencies for Brum include Vivid Project (digital media/film); Grand Union (VA), Styrx (VA), Homes for Waifs and Strays (Live Art), Centrala (Polish cultural centre) who now play host to national festivals such as Fierce Live Art; Flatpack Cinema and Supersonic experimental music. This is all organized internally and supported by Colliers as site managers.

- Independent Review and Appraisal With the client, I commissioned an independent report in autumn 2014 by Dr Rachael Unsworth at the University of Leeds on the characteristics of the regeneration of Warwick Bar which were framed up as ‘slow architecture’ in that we are creating a structure or ensemble of structures gradually and organically with regard to sustainability criteria, as opposed to rapid construction to achieve short-term goals. We define structures as systems, governance, relationships and value here.

- Policy and Future Proofing We are using the report now as a provocation to the city and Digbeth in the face of HS2 major investment and being tactical about the future, we are supporting the setup of the Digbeth Business Investment District in ways to ensure the representation of micro and small businesses that predominate the manufacture and cultural sectors in the area.

- Linking to HEIs Now the 43,000 square feet of lettable space is almost fully occupied, I am building on what is there by developing a partnership with Birmingham City University’s Cross Innovation Unit to support the emergent intra-trading and collaboration that happens onsite. Again it is the diversity of companies, commercial and not-for-profit, around manufacture, fabrication and creative/digital agglomeration, with the collegiate culture, that underpins emergent trading/sharing activity.

Issues arising

- Creating and building densely Interconnected networks (infrastructure) which self generate and have their own sense of future ambition (beyond my/our involvement)

- Creating permissive and responsive governance and policy that is ‘porous’

- How to get it right for now but plan for the future and avoid short-termism

- How to find the right balance between creativity of emergence and stability of design

- How to prevent a ‘toolkit approach’ when processes are scaled up or transferred.

MAAP online portfolio www.maap.org.uk

1. Interview with Monika Büscher

Q: Please summarise your current or previous research.

A: My research explores the digital dimension of contemporary ‘mobile lives’ with a focus on IT ethics. Information and comunication technologies are an integral part of everyday life and often central to societies’ answers to the complex challenges of the 21st Century. Efforts to decarbonise transport and energy, improve health and well-being and enhance security often assume that more of the right information at the right time can enhance efficiency and change behaviour. Yet informational and communicative mobilities are not innocent. Based in the mobilties.lab, I combine qualitative, often ethnographic studies, social theory, and design through mobile methods, experimental, inventive, disclosive approaches, and engagement with industry and diverse publics to design IT for ‘good’. This research is interdisciplinary, experimental, engaged ‘public sociology’ that produces insights and methodologies to explore and shape socio-technical futures. I have a long- standing interest in design for design and design for ‘infrastructuring’, that is, designing in ways that enables people to make (technical, but also social, political) infrastructures ‘palpable’. My most recent research brings this perspective to the informationalization of ‘smart cities’ and disaster mobilities, which affords new forms of knowledge, command and control, public engagement, emergency planning and emergency response. Opportunities include emergent interoperability, agile and ‘whole community’ approaches, collective intelligence and data sharing, while challenges arise around data protection, privacy, social sorting, automation, technologically augmented human reasoning and action at a distance (SecInCore and BRIDGE projects). My colleagues and I are using concepts of relational ethics and cyborg phenomenology to inform innovation.

Q: Are there any groups/institutions you have not previously collaborated with but think it would be helpful to do so?

A: I currently work mostly with publics who have declared an interest in the design of IT infrastructures and technologies, ranging from healthcare and disaster response professionals to ad-hoc social media publics to policy-makers. But the ethical, legal and social issues arising have much wider importance. For example, literally everyone is affected by the design of systems that enable emergent interoperability and data sharing in ‘common information spaces’. As different institutions and agencies involved in transport, emergency planning and emergency response (including operators and control centres, social, police, fire and healthcare services, local authorities and government organisations) are invited to shape innovation, research related to ‘the wider public’ is too often about how education and design can foster more wide-spread ‘acceptance’, when it should be about ‘acceptability’ (see, e.g. Boucher 2014). I would like to work with publics and/or researchers and projects:

- to collectively identify risks, intended, unintended, and emergent systemic consequences of IT innovation in everyday life

- to study and shape everyday creativity and social innovation that can mitigate risks and negative consequences

- to maximise the potential of IT to become part of more equal, enjoyable, effective futures, respectful of environmental, social, political, moral and cultural values.

Q: How do you see design and social innovation being linked?

A: Social innovation is both a source of momentum and direction for design and an important site of design in its own right. Recognising the temporal and spatial multi-sitedness of design opens up questions about expertise, knowledge, power, control, ignorance, responsibility, response-ability, located accountabilities, context, and method. It also raises questions about the object of design. My work is about designing and analysing socio-technical ‘things’ or futures – assemblies or configurations of social practices, imaginaries, technologies, material worlds, regulatory frameworks, policies. This is never-ending ‘disruptive’ innovation, inevitably accompanied by positive and negative effects, which emerge in the making and inhabiting of futures. It is one of the main responsibilities of sociological enquiry, in my view, to study and evaluate emergent future practices and effects of such reconfigurations, to fold insights into design at (ideally) all its locations, and to help to fairly put those with an interest in a position to notice, influence, at least debate, at best ‘control’ the morality of innovation.

Q: What is distributed collaboration and how does it best function as a research mode?

A: Distributed collaboration is a necessary mode of doing the research co-creation, collaborative design, collective experimentation, and contestation of futures that is needed to define and make innovation ‘good’. Things – analysis, design, social innovation – happen in different places and at different times. To synchronise them intensely collaborative and postdisciplinary methods are needed. Methods that bring together multiple perspectives and modes of knowledge and expertise, that disclose specific articulations of agency at different places in the system, and that enable reflective practice, experimentation and mutual learning by doing have worked best for me. They include prototyping, provotyping, living laboratories, co-design, critical, speculative design, value sensitive design, disclosive ethics, ethical and privacy impact assessment, forms of experimentation that allow multiple actors to reflectively inhabit futures.

Q: What is interoperability and can it function in social design?

A: Interoperability is a socio-technical concept that seems to travel across many fields. The US Department of Homeland Security recognises that ‘jurisdictions must connect technology, people, and organizations to achieve interoperability’. Interoperability may emerge as a temporary effect of the processes and practices people and organizations employ to collaborate, but it is also an effect of technical and material agency, so design and infrastucturing matters, and interoperability is not singularly benign. In the exceptional circumstances of a disaster, a commitment to connection between the multiple agencies involved may be desirable. However, when and where does the disaster stop? And who decides? How far do we allow preventative logics to shape our capacities to notice and resist surveillance? What does this do to what it means to be human, freedom and equality? ‘Good’ interoperability between technologies, people and organizations involved in social design, design, and analysis requires concepts and policy and technology support for practices of collaboration, debate and dialog, that allow attention to frictions, multiplicities, located accountabilities, response-abilities and ways of ‘cutting the network’.

Is there a question you would like us to ask another ProtoPublics participant?

Do you ‘scale up’ your practices of research co-creation, experimentation, collaborative design to go beyond localised participatory projects to meet the ‘grand challenges’ of the 21st Century? Is it possible/necessary to design our way out of complex, global and interconnected problems like climate change and surveillance at other than local scales? If you do it, how do you do it? If you don’t why not?

Selected References

Bannon, L. and Bødker, S. (1997). Constructing Common Information Spaces. Hughes, J. et al. (eds), Proceedings of the Fifth European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 81-96. Kluwer.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham: Duke University Press.

Boucher, P. (2014). Domesticating the Drone: The Demilitarisation of Unmanned Aircraft for Civil Markets. Science and Engineering Ethics. doi:10.1007/s11948-014-9603-3

Burawoy, M. (2005). For Public Sociology. American Sociological Review, 70(1), 4–28.

Büscher, M., Urry, J., Witchger, K. (2011). Mobile Methods. London: Routledge.

Chapman, O. and Sawchuk, K. (2012) Research-Creation: Intervention, Analysis and ‘Family Resemblances’. Canadian Journal of Communication, Vol 37, No 1 (5-26).

Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Ehn, P. (2008). Participation in design things. In PDC ’08 Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design 2008, Indiana University (pp. 92–101). Indianapolis. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1795234.1795248

Elliot, A., & Urry, J. (2010). Mobile Lives. London: Routledge.

Felt, U. and Wynne, B. (2008). Taking European Knowledge Society Seriously: Report of the Expert Group on Science and Governance to the Science, Economy and … for Research, European Commission, Directorate-General for Research, Science, Economy and Society.

Fuller, M. (2008). Software Studies: A Lexicon. MIT Press.

Greenhough B. and Roe E. (2010) From ethical principles to response-able practice. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28(1) 43 – 45.

Hartswood, M., Procter, R., Slack, R., Voß, A., Buscher, M., Rouncefield, M., & Rouchy, P. (2002). Co-realization: toward a principled synthesis of ethnomethodology and participatory design. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 14(2), 9–30. doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-901-9_3 http://aisel.aisnet.org/sjis/vol14/iss2/2/

Kimbell, L. (2013). An inventive practice perspective on designing An Inventive Practice Perspective on Designing. PhD Design, Lancaster University. Lancaster University.

Lury, C., & Wakeford, N. (2012). Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social. London: Routledge.

Mendonça, D., Jefferson, T., & Harrald, J. (2007). Emergent Interoperability : Collaborative Adhocracies and Mix and Match Technologies in Emergency Management. Communications of the ACM, 50(3), 44–49. doi:10.1145/1226736.1226764

Mogensen, P. (1992). Towards a provotyping approach in systems development. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 4(1), 31–53.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. Basic Books.

Star, S,L. & Bowker, G. 2002. How to Infrastructure. In L. A. Lievrouw, L.A. & Livingstone, S.L. (eds.) The Handbook of New Media, London: SAGE, 151-162.

Storni, C. (2013). Design for future uses: Pluralism, fetishism and ignorance. Nordic Design Research Conference 2013, Copenhagen-Malmö (pp.50-59).

Strathern, M. (1996). Cutting the network. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 517-535.

Suchman, L. (2002). Located accountabilities in technology production. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems – Special Issue on Ethnography and Intervention Archive, 14(2), 91–105.

Thackara, J. (2005) In the Bubble: designing in a complex world. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

US Department of Homeland Security, & The US Department of Homeland Security. (2004). The System of Systems Approach for Interoperable Communications. Available from http://www.npstc.org/download.jsp?tableId=37&column=217&id=2458&file=SOSApproachforInteroperableCommunications_02.pdf [Accessed 13 March 2015]

Von Schomberg, R. (2013). A vision of responsible innovation. In R. Owen, J. Bessant, & M. Heintz (Eds.), Responsible innovation. London: Wiley.

2. Interview with Justin Spinney

Justin Spinney is lecturer in human geography at the University of Cardiff. In this interview, which we conducted over email, he reflects on his work on mobilities and transport, his application of ethnography in relation to design research and the groups and communities he would like to be able to engage with more through his work.

Tell me briefly about your current or previous research.

The main project I am currently working on is the cross council funded Cycle Boom project. Working across 4 UK cities this project seeks to build up a better picture of cycling in older age with specific reference to the ways in which urban design and new technology (such as e-bikes) can get more older people enjoying cycling. A particular focus for me is ways in which we can understand and measure affect and emotional experience and design environments which promote positive affect rather than simply minimising negative affects.

In addition to this I am also working on a project on HGV design. HGVs are over-represented in collisions with cyclists and pedestrians on European roads, partly because of mass and speed but also because of a design which gives very little direct visibility. I am interested in the effect on drivers of new visual safety technologies – do they for example create ‘sensory overload’ possibly making driving less safe? In addition, I am interested in the passage of new EU safety regulations to modify HGV design, and the ways in which this is being shaped by different stakeholders.

Previous research has looked at the materialities of parenthood, in particular the ways in which objects such as buggies and slings shape the experiences, identities and mobility patterns of new mothers.

Can you identify a group/institution you have not previously worked or collaborated with, but think it might be helpful to do so?

I would very much like to work with car/motorcycle/bicycle manufacturers to look at the possibilities of creating a new kind of ‘bicycle’ which would deviate from the normalised bicycle and encourage more people to cycle who do not currently identify with it for various reasons. Another group who I believe are very important are design students. So to forge partnerships with the RCA, Coventry and Loughborough would also be very productive.

How can we think about mobilities in radical ways?

I believe we need to think through mobility in two inter-related ways. Both of these relate to the ways in which mobility is represented and normalised as this and not that. In much of the Global North we have currently normalised driving because of what it offers us in relation to the ways in which our lives are currently configured. Driving does indeed have many benefits. The challenge is to transfer (through design) the best of these (comfort, care, convenience) to a new breed of ‘vehicle’ whilst leaving the worst (pollution, congestion, harm, sedentarism).

In doing so we are not only attempting to shift the practices of mobility, but also the meanings of mobility. For non (or less-motorised) transport to be successful requires a shift in meanings that is rooted in the alternative practice and representation of mobility. We need positive role models for alternative mobilities rather than the discourses of eccentricity which emerge around new forms of mobility (think Segway and Sinclair C5!).

One of the goals here is to develop more inclusive forms of mobility. Our current vision for cycling in the UK for example currently excludes many people on health, social and cultural grounds. A different approach to design that facilitates new forms of practice and meaning can also engender a more inclusive and equitable politics of mobility.

What are the limits of considering affect in your research field?

Two of the questions I am currently grappling with in the EPSRC Cycle Boom project are how do affects arise and how can we measure them? One of the limitations is how to understand something which has multiple and fleeting influences – it is impossible to isolate ‘variables’ as such so the best we can do is ask participants to relate particular experiences to phenomena. The picture this gives however is far from complete. As a result one of the things we are trying to do is quantitatively measure and map affect using mobile Electroencephalography (EEG) and GIS. This offers up the possibility of bodies ‘speaking for themselves’ and offering less rationalised accounts of emotional and affective experience. However there are also considerable limitations in doing so, not least because the technology we have to measure such experiences whilst mobile is inferior to that available in laboratory settings.

Do you see limitations in the application of ethnography in design research?

I am a big fan of ethnography in design research; I believe if done well it can facilitate a much more grounded understanding of use than (for example) the focus group. In order to do this however requires a great understanding of people’s everyday lives – we cannot look at how people use a particular object in its context of use, rather we need to see how it relates (or doesn’t) to other aspects of life. There are of course limitations. It is time consuming and requires ‘attunement’ of the researcher to the context. It also requires great collaboration between researcher and participant in order to ensure correctness of interpretations.

You use the term ‘destabilisation’…what does it mean and how can this operate in design for collective societal ends?

This relates to my previous point regarding the ways in which norms regarding mobility become sedimented. For example why are ‘cars’ so narrowly conceived as metal boxes with four wheels and a motor? Why are bicycles so narrowly conceived as having two wheels, no motor, no protection from the elements? I believe we need to de-stabilise, upset and over-turn these myopic classifications and find many more hybrids that can break us out of current mobility patterns.

Interview by Leah Armstrong and Guy Julier for ProtoPublics.org